Turcica in North and Central European Libraries and Kunstkammers

Ottoman objects made their way into Central European Early Modern libraries and Kunstkammers (art cabinets), or curiosity cabinets in many ways, including as manuscripts, armour and costumes. The aim of this paper is to contribute to an overview of the types of works collected and how they were categorised and catalogued within a group of important court collections from Central and Northern Europe. I will consider objects from collections in Vienna, Innsbruck, and Prague, and offer comparisons between these and Kunstkammer and library collections in Munich, Dresden, Wolfenbüttel, and Copenhagen. These highlight several of the ways the Ottoman Empire was perceived in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It is part of an ongoing project, which focusses on library catalogues and Kunstkammer inventories in order to find the connections between theological, intellectual, military and scientific discourse in Europe and perceptions of the Ottoman Empire. These collections have been studied, especially in the context of individual museums or museum exhibitions, though little comparison has been made on books and manuscripts alongside the costumes, military regalia, and other material objects in the collections.1 I aim to establish how these inventories, catalogues, and lists serve to forge new connections, themes, and conceptions of the Ottoman Empire through the medium of Central and Northern European courts and court networks.2

The display and fascination with the Ottoman Empire also appears in many images and figures created by European artists. Presented here is a mysterious world completely unknown to the artist and often to the viewer. Inspired by material brought back from the Ottoman Empire itself, robed sultans, or powerful warriors, often take centre stage. The standing figure clock from the Hapsburg Kunstkammer collections, produced in Augsburg around the period 1580 to 1590, now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, is a case in point (fig. 1).3

This is an example of the late sixteenth-century tradition of automated clocks with delicate goldsmith work and it encapsulates many of the ideas about the Ottoman Empire present in Central Europe at this time.4 It showcases the opulent, upright figure of the Sultan, standing in the middle of a boat, guarded by a soldier with a scimitar and rowed by a turbaned man. A monkey sits mischievously at the golden prow, contributing to the idea of distant lands and the many riches within them.

Manuscripts and objects related to Islam and the Ottoman Empire also presented such opulence and display. This material had been in court and monastery libraries in Central and Northern Europe from the times of the Crusades, and later from the time of the Fall or Capture of Constantinople in 1453.5 It was from the late sixteenth century that texts by scholars and theologians directly analysing the Ottoman Empire began to figure strongly in court libraries in Central and Northern Europe. This was a direct result of the wars between Hapsburg and Ottoman armies over Hungarian territory, in the 1520s, 1540s and 1556 together with the so-called long Ottoman wars of the 1590s into the seventeenth century, which culminated in the 1683 Battle of Vienna.6 In addition, direct diplomacy from the 1530s onwards, together with trade networks and the growing importance of book and art agents, who worked for the courts such as the Augsburg agent Philip Hainofer (1578–1624), resulted in an influx of Ottoman material.7

The Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, was amongst the earliest to incorporate Ottoman objects into a central European court collection. His collection largely originated from his role as leader of the Hapsburg armies in the wars against the Ottoman Empire. Ferdinand had been made King of Bohemia and Hungary in 1526, after the death of King Louis of Hungary at the Battle of Mohačs. While the Hungarian territory was divided following an Ottoman-Hapsburg truce in 1533, this only lasted until 1537 after the attempted re-capture of Ottoman territory. At this stage John Zápolya, Prince of Transylvania, was made king following a treaty with the Ottoman Empire. After his death in 1540 the Ottoman Empire annexed most of the Hungarian territory, which became a province after the Siege of Ofen or Buda in 1541.8 As King of Hungary, Ferdinand became one of the sixteenth-century rulers most associated with the wars over Ottoman territory, even more so after having been crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 1558.9 Weapons and war booty, ranging from bows, arrows, daggers and scimitars to janissary hats, harnesses, saddles and carpets, made up the largest proportion of the Islamic and Ottoman objects in his collection.10 The Ottoman Bow and Arrow and Janissary Hat, from circa 1550, now on display in the Kunsthistorisches Museum are key examples.11 Ferdinand I’s acquisitions in turn were distributed amongst his three sons, Emperor Maximillian II, Archduke Ferdinand II and Archduke Karl II. They then went on to become key parts of other Hapsburg Imperial and Ducal collections, including those of Ambras, Gratz, Vienna and later Prague.12 Furthermore, Ottoman costume, weaponry and associated diplomatic gifts linked to Charles V feature strongly in the Hapsburg collections.13

Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol’s Kunstkammer at Schloss Ambras was one of the first museum collections to feature a Türkenkammerl or small Turkish chamber within his ‘Rüstkammer’ (Armoury). Many of the objects were inherited from his father, Emperor Ferdinand I, as was the position of Governor of Tyrol itself.14 The chamber included many objects from the wars against the Ottoman Empire over Hungarian territory from the 1520s to the 1590s and even became the focus of manuscripts, such as the Turnierbuch, Erzherzog Ferdinand II.15 Several of the military objects were brought back from Ferdinand II’s Imperial Campaign against the Ottoman armies in 1556. Other military objects in this collection derived from Lazarus von Schwendi, the diplomat and general who fought in Hungarian territory from 1564 onwards.16 The Kunstkammer and Armoury was housed in the Lower Castle or Unterschloss with three buildings dedicated to the ‘Rüstkammer’ and a fourth to the other collections of the Kunstkammer. They were chronicled in detail in the inventory of his collections from 1596, organised along the principles of material, as influenced by the collections of Francisco de’ Medici of Florence. However, many areas of the Kunstkammer included Ottoman objects in the categories of jewellery, ornaments, textiles, and especially weaponry.17

As court historian to Albrecht V of Bavaria, Samuel Quiccheberg specifically formed his early museum categories around the Munich collections, where Ottoman objects featured in all five classes of the Kunstkammer.18 Owing to the strong marital connections between the Hapsburg and Wittelsbach families, these collections contained a great deal of Ottoman material.19 Quiccheberg’s categories became standard in the growing museums tradition. They were arranged into five classes: 1) Religious paintings, art related to theatre, together with material related to history and geography, models and machines;20 2) Portraits, artwork in metal, wood, stone and glass, engravings and sculpture, as well as coins and medallions;21 3) Natural history, including animals, birds, insects and fish, plants, precious and non-precious stones and pigments;22 4) Science, mechanics (including musical instruments) arms and armour;23 5) Paintings, drawings, prints, engravings, family trees, heraldry, textiles and furnishings.24 Ottoman objects and Turcica featured across most of these categories in various forms.

The first Hapsburg inventory to reflect the structure of Quiccheberg’s order was the Kunstkammer of Rudolf II, which began before his appointment as Holy Roman Emperor in 1576 and was fully established after the Court was moved to Prague in 1583. The collection itself is once again strong in Turcica and Ottoman objects, as a consequence of the strong diplomatic and later military connections with the Ottoman Empire, and it contained many objects inherited from Rudolf’s father Emperor Maximilian II and grandfather Emperor Ferdinand I.25 The collection itself very much reflected the wars against the Ottoman Empire, especially the armoury, which was juxtaposed with the Hapsburg weapons of the period.26 Stability officially remained within Hungarian territory at this time, marked by a cease-fire and a tributary gift sent to the Sultan each year.27 However, with the end of the Ottoman-Persian wars in 1592, open struggle for territorial power between the Hapsburg and Ottoman forces re-commenced. The Hapsburg victory at the Battle of Sisak in Croatia in June of 1593 marked the beginning of the Long Turkish War (1593–1606). This victory was commemorated in several pamphlet illustrations, single prints and even bronze reliefs for Emperor Rudolf II, which made up part of his collections.28 Collections include a brass relief of the battle by Adrian de Vries, based on an oil sketch forming part of a series by Rudolf II’s court painter Hans von Aachen’s workshop.29 This image is an allegory of the battle and re-gaining of the Fortress of Raab or Györ in 1598 (fig. 2).30

The background features armed Ottoman and Hapsburg cavalry together with the fortress of Raab. In the midground the Seven Headed Beast of the Apocalypse represents the Ottoman threat, whilst in the foreground a battle takes place between the Holy Roman Lion and the Ottoman Dragon, surrounded by classically dressed figures.31

Although many of the objects in Rudolf II’s collections were inherited from his forefathers, the number relating to Ottoman Empire increased during his rule, as is apparent in his collection inventory from 1607–1611, which reflected Quiccheberg’s categories.32 Like the earlier collections, many of the objects were military, consisting of bows, arrows, daggers and scimitars, along with firearms of modern warfare. They also included a variety of diplomatic gifts, such as the leather drinking flask (Feldflasche) gifted to Rudolf II by Sultan Murad III, along with an invitation to the celebration of the circumcision of the latter’s son in 1581.33 This was a major extension to the earlier diplomatic material of Hapsburg courts from the time of Ferdinand I’s collections, which had included several items brought back from Constantinople on diplomatic trips between 1554 and 1562. In turn, Ottoman items from the Hapsburg collection also made their way to other courts, including Dresden, in the seventeenth century.34

Another form of diplomacy, namely the strong family and marriage ties between the Hapsburg and Wittelsbach families, facilitated the transfer of Ottoman objects into the Munich collections.35 This can be seen in the Munich Kunstkammer inventory from 1598, which includes costume, drinking flasks, manuscripts and books with Ottoman script and illustrations.36 Other collections with large sections of Ottoman costume and clothing were often closely tied to specific military or naval battles in the Hapsburg and Venetian struggles against the Ottoman Empire. For instance, over fifty Ottoman objects in the Copenhagen Kunstkammer collections, including weapons and military regalia, can be traced back to Cort Adler, an admiral who fought in the Venetian wars. The 1737 registry of the collections details these objects in the volume of ‘Indian’ or Oriental works. They range from a plaque with the victories of Admiral Adler in 1658 to specific objects including: scimitars, equestrian paraphernalia, battle axes, guns and janissary headwear.37 Such material provides a glimpse into the fascination and memories of not only battles and warfare, but also costumes and life in the Ottoman Empire, Constantinople, its court and city together with the people, their lives and religion.

The costumes collected through travel and diplomacy also provided examples of the diverse culture of the Ottoman Empire, beyond the Islamic religion. Examples are Orthodox Greek objects in the collections, including a vestment, from Istanbul or Bursa from the sixteenth century.38 This vestment, made of silk, and forming part of the ritual of the Orthodox Church, indicates the strong remaining presence of the Orthodox Greek Church in the Ottoman Empire. Such objects relating to religious rituals fascinated humanist trained scholars and collectors of the Central European courts, both for the connections to the Roman Empire and to the many faiths in the Ottoman Empire itself.

Weapons, armour and associated costume, as well as Turcica in library, manuscript and print collections can sometimes be closely identified with specific battles. An instance is the 1552 campaign by Duke Moritz of Saxony.39 Objects related to this campaign feature in the large sections containing bows, arrows, and other weapons from the 1587 Dresden Catalogue onwards.40 Diplomatic gifts also made up large parts of the Dresden collection. For instance in each inventory, several pages are dedicated to presents relating to the Ottoman Empire from Italian Dukes, including the Medici and Gonzaga families.41 In addition, the 1619 Inventory also details Ottoman and other exotic gifts from Duke Charles and other Hapsburg rulers, acknowledging the assistance from Duke Christian II of Saxony during the long Turkish Wars (1593–1606).42 By the late seventeenth century there were enough Ottoman objects in the Dresden Kunstkammer to warrant a catalogue solely devoted to these items.43

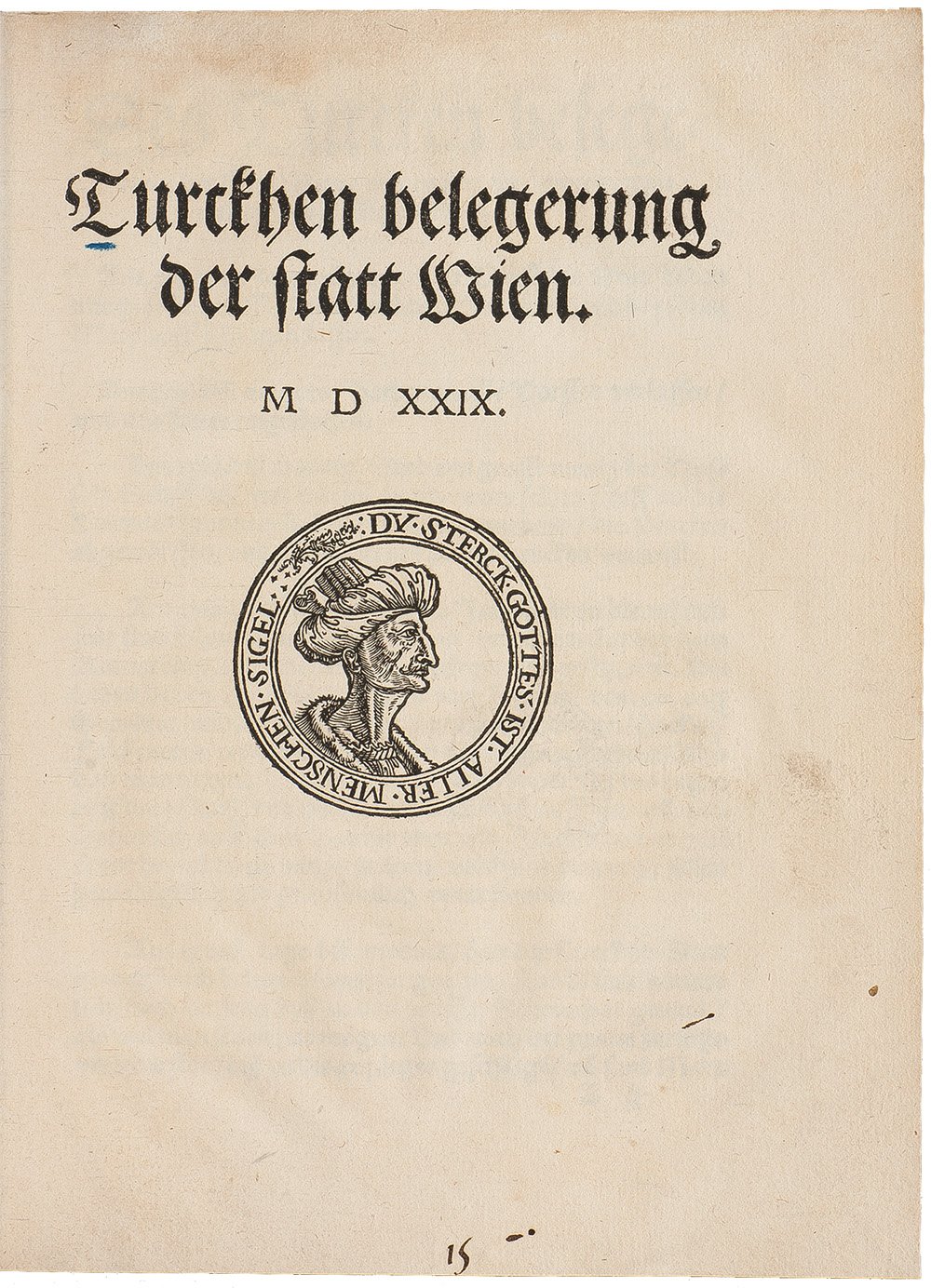

Objects and costumes collected during this time also strongly influenced the depictions and descriptions of the Ottoman Empire far beyond the realm of the court and across a wide variety of media available to a broader viewership. For instance, many pamphlets relied on the medallion portraits of the Ottoman Sultans. An early example is the medallion portrait of Sultan Suleyman II, produced after 1521, seen in pamphlets such as Turckhen belegerung der statt Wien (fig. 3).44 Medallions were easily transportable and could be copied and re-cast at a rapid rate. These medallion portraits were a chief method of enabling the transfer and recognition of the images of the Sultan beyond any collection where they were housed and helped the sultan’s image become part of the broader consciousness.

Coin and medal collections were also important within the Kunstkammer tradition, often produced and re-produced from artworks by Venetian artists, including Gentile Bellini. For instance, they made up a large part of the collections in Ambras, Vienna, Munich and Prague.45 Such medallion portraits were in turn re-used to illustrate pamphlets throughout the later parts of the sixteenth century and into the beginning of the seventeenth, though many of the medallions were sourced from the earlier decades. However, these pamphlets now reported battles and skirmishes between Ottoman and Hapsburg forces rather than stories about the Sultans or the Ottoman court.46 In addition, increased contact between Ottoman and Hapsburg forces meant increased familiarity with Ottoman armour and weaponry for artists, linked to the ducal and princely Kunstkammer collections.47

The inclusion of costume in the court collections was established through travel literature, costume books and manuscripts produced by both European and Ottoman artists, together with Ottoman manuscripts of many other types brought to Central European libraries and published as print series. Ottoman manuscripts, produced specifically for Christian European markets – sometimes even by European artists, became more common following the increased travel to the Ottoman Empire in the second half of the sixteenth century.48 Examples were collected or produced by scholars, theologians and diplomats such as David Ungnad von Sonnegg, Lambert de Vos, Salomon Schweigger, Johannes Löwenclau and Ogier Ghislan de Busbeq.49 Further examples were introduced through trade and trade networks, especially in Venetian and Hungarian territories, with many eventually purchased in cities such as Nuremberg or by art agents working for the court.50 These illustrations in manuscripts influenced Northern European printed costume studies. Examples are now located in major European collections, including Bremen, Dresden, London and Oxford.51 These books were often considered part of the Kunstkammer, rather than the libraries, which were beginning to be catalogued separately at this time.52

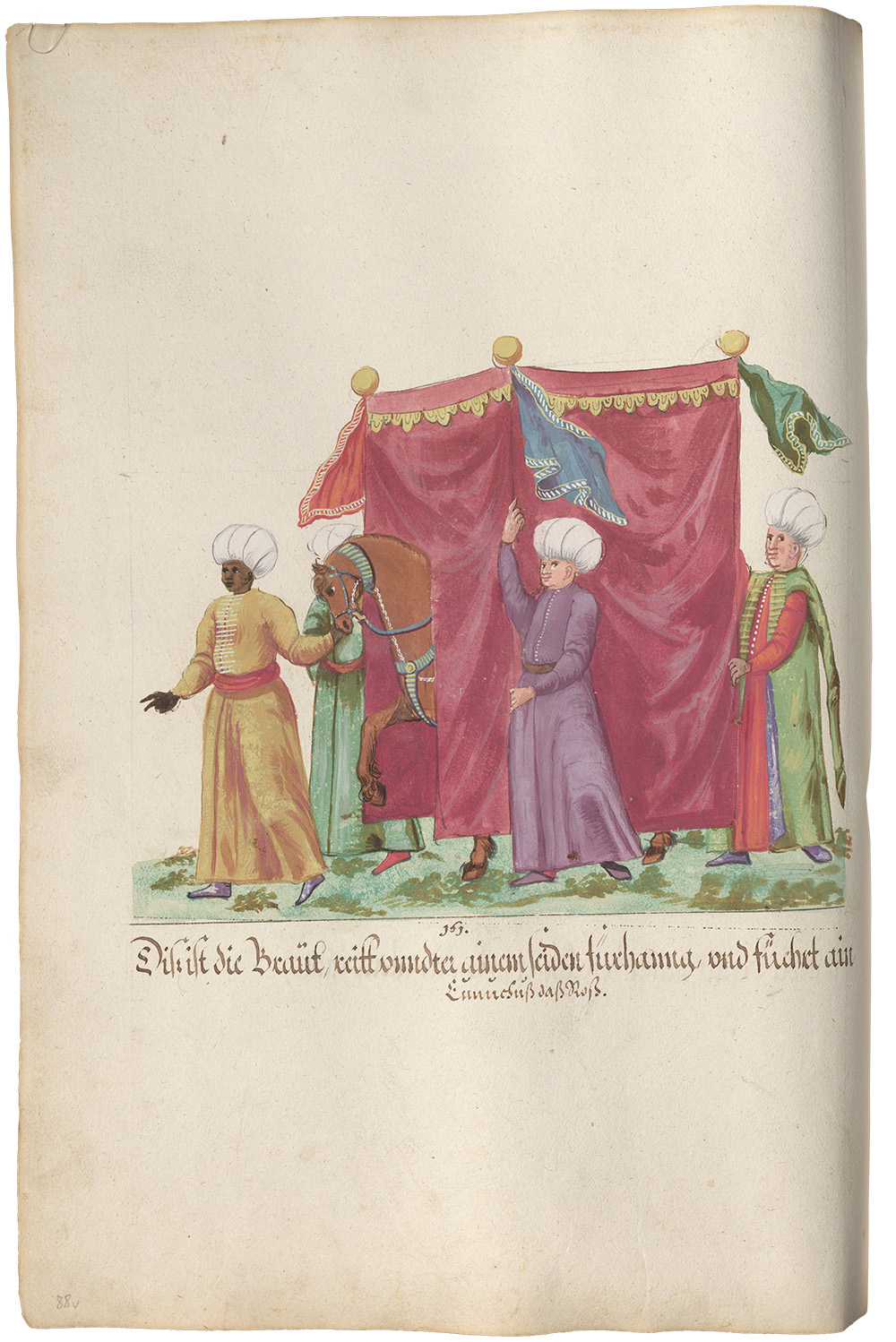

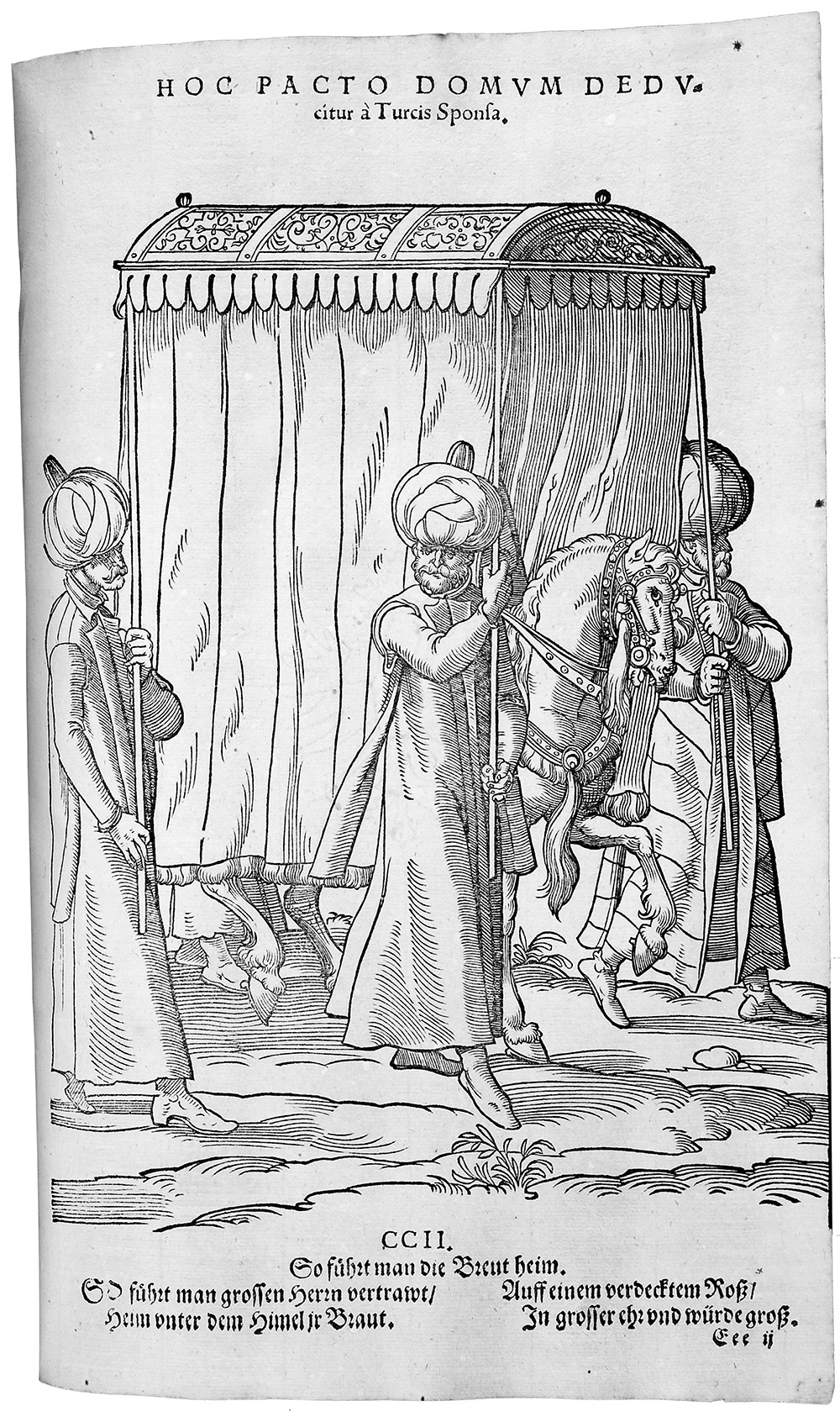

Such images directly influenced printed works of the day, including costume books featuring peoples of the world. For example, the many direct similarities between Jost Amman’s illustrations to Habitus praecipuorum populorum and a group of linked manuscripts, including the Vienna Codex 8615, indicate cultural and artistic awareness of this source group. The most direct similarities between Codex 8615 and Habitus praecipuorum populorum relate to the layout of the images. For instance, in both we see an image of a bride being borne on horseback, with associated text describing the event.53 The text in Codex 8615 (fig. 4) gives a short German explanation, whilst Habitus praecipuorum populorum (fig. 5) includes the Latin title Hoc Pacto Domum Deducitur à Turcis Sponsa above the image, with a more elaborate German vernacular poem below: “So führt man die Braut heim./ So führt man grossen Hern vertrawt/ Heim unter dem Himel ir Braut./ Auff einem verdecktem Rosz/ In grosser ehrr/ und würde grosz.” (This is how the Bride is borne home/ So does one take home wives betrothed to great lords / home under the canopy/ on a covered horse/ in great honour) [figs. 4 and 5].54

Images of the bride being carried home feature in many similar manuscripts, including works created and illustrated by writers and artists such as Salomon Schweigger and Zacharias Wehme. Outside the costume books, official festivals in the courts and cities of Northern and Central Europe exhibited costume of the Ottoman Empire. An instance is the attendance of the Ottoman Ambassador during the festivities for the Coronation of Maximillian II as King of the Romans in Frankfurt in 1562.55 Ottoman costumes were further used as source material in a variety of contexts, including court processions and festivals well into the seventeenth century.56

Many costume books, together with illustrated and text-based manuscripts from the Ottoman Empire, were catalogued in Kunstkammer collections in sections related to printed texts, or prints and drawings. An example is the 1598 Munich inventory, which also indicates the growing presence of books related to Islam, wars against Ottoman armies and culture and society of the Ottoman Empire.57

The work of Hugo Blotius, Court Librarian in Vienna under Maximillian II from 1575, stands out as a key example in the overall organisation of texts relating to Ottoman themes. After the coronation of Rudolf II in 1576, the same year in which he became Professor of Eloquence at the University of Vienna, Blotius undertook to catalogue the Ottoman manuscripts in the library.58 This first catalogue relating specifically to the Ottomans was compiled in 1576 and focussed on the Court Library in Vienna and five other private Libraries. The title begins Librorum et orationum de Turcis et contra Turcas latine scriptae.59 A key reason for this compilation by Blotius was to present information useful for the Christian Republic in its struggle against the Turk, to offer special military tactics against the enemy and to show how the war could be supported and sustained. In creating such a catalogue, Blotius bolstered the political significance of Court Librarian in a time of political turmoil. Further, as a Calvinist in a Catholic court, he perhaps sought to retain his job, though he converted to Catholicism in the same year.60

The catalogue Librorum et orationum de Turcis et contra Turcas begins with theological texts about the Ottoman Empire in Latin. They are set out in alphabetical order and prominently feature writings by Aeneas Silvius (Pope Pius II) and other orations and speeches of the Catholic Church against the expanding Ottoman Empire. These texts are theological, historical or scholarly in nature, including commentary on the Quran, rather than the popular pamphlets and newssheets also being published at the time. Though it also contains material by Martin Luther, the catalogue adopts the focus of a Catholic library and Catholic view of the Ottoman Empire.61

In contrast, Duke August, who was Elector of Saxony between 1553 and 1586, took advice from professors at the Lutheran Universities of Wittenberg and Leipzig in assembling his library.62 He also included several texts written by Lutheran theologians on Ottomans in the theological section of his library, labelled “Von Türcken” on folio 29v in his 1574 Catalogue Registratur der bucher in des Churfursten zu Saxen liberey.63 Here the short selection of texts focusses on both the military and religious threat of the Ottoman Empire. It has a strong Wittenberg and Lutheran theological emphasis, with texts in both Latin and German. For instance, it includes the Latin translation of the Quran by Ricoldo de Monte Croce, with an introduction by Martin Luther. The Quran was not published in German until 1616 by the Lutheran Theologian Saloman Schweigger, and from this time onwards his translation was in library collections.64 Other works in the Registratur are Martin Luther’s 1529 work, On War against the Turk, as well as texts by Johannes Brenz and Philip Melanchthon on the Ottoman Empire. It should also be noted that the Registratur contains several other books on the Ottoman Empire, its people and armies. These include chronicles, histories, geographical works (including travel literature) and especially military texts. However, these volumes are not grouped together in a specific section, unlike those in the theology section.

Other contemporary catalogues from Lutheran courts, including that of Herzog Julius of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, created in 1613 or 1614, over 20 years after his death in 1589, also focusses on Lutheran texts, though not specifically on the Ottoman Empire.65 In the seventeenth century, the expanding catalogues were also re-organised to fit the humanist themes behind the growing court collections, related universities and their associated scholarly communities. They include the University of Helmstedt with Wolfenbüttel or the Universities of Leipzig and Wittenberg with Dresden.66 Within the library catalogues, the categories of theology, legal history, medicine, history, philosophy, mathematics, philology, architecture, agriculture, poetry, music and grammar became particularly prominent. Books about the Ottoman Empire appear in many of these, though most predominantly in the theological, military, historical and geographical sections.

Scholarly manuscripts and religious texts played a central role within the growing library collections, alongside printed texts published by authors writing in Latin, German and Italian on the theological and historical issues of Islam. An example is the 14th-century Quran, which was originally part of the humanist Johann Albrecht Widmanstetter’s collection, probably purchased in Italy, and directly related to his own 1543 translation into Latin.67 Albrecht V of Bavaria purchased the manuscript in 1588 in order to bring knowledge about Islam and the Near East to the court and visitors to his library. The books in Widmanstetter’s collection had mostly been purchased in Italy, though several originated in the Ottoman Empire.68 Albrecht V’s acquisition of these manuscripts shows the desire for knowledge, often borne out of the need to explain the differences between Christianity and the perceived dangers of Islam, as well as a sense of curiosity about the rituals and religious displays of this little known world. Such Islamic decorative and religious works are further found in other corresponding library collections, including the library catalogues of Vienna, such as the Librorum et orationum de Turcis et contra Turcas and Dresden, including the Registratur der bucher in des Churfursten zu Saxen liberey.69

Medical and astronomical texts also became important within the transfer of knowledge and understanding from the Ottoman Empire and the broader Islamic world to Central and Northern European courts. Many astronomical and scientific texts, both Ottoman and Arabic, became a source to new scientific and medical thought within the enlightenment movement. For instance, the manuscripts brought back by the Danish Arabia Expedition, led by Carsten Niebuhr between 1761 to 1767, provided key texts to scientific studies for the court and scholarly community of Copenhagen.70

In conclusion, the period between the mid sixteenth and mid eighteenth centuries saw a strong acquisition program of Ottoman and Ottoman-related material or Turcica by major court Kunstkammer and Library Collections in Central and Northern Europe. This paper has outlined some of the most significant areas and catalogues highlighting Ottoman objects and associated manuscripts within Early Modern Central and Northern European Kunstkammer and library collections. It has demonstrated how these provide keys to the interaction between the Near Eastern and Central and Northern European World. The areas of costume, theology, science and religion all represent the gathering and display of knowledge about the broader and unknown world to Central and Northern European courts and associated scholarly communities. Their cataloguing and display highlight the connection between the objects, their collectors, and the broader scholarly and artistic community surrounding the court.

Bibliography

Alhussein, Alhaidary Ali Abd and Stig T. Rasmussen. Catalogue of Arabic Manuscripts in the Royal Library, Copenhagen: Codices Arabici Additamenta & Codices Simonseniani Arabici. Copenhagen: The Royal Library, Munksgaard, 1995.

Bauer, Rotraud and Herbert Haupt, eds. “Das Kunstkammerinventar Kaiser Rudolfs II. 1607–1611.”Jahrbuch der kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien 72 (1976): 281–345.

Blotius, Hugo. Librorum et orationum de Turcis et contra Turcas scriptorium. (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 15303 Han).

Bohnstedt, John. “The Infidel Scourge of God: The Turkish Menace as seen by German Pamphleteers of the Reformation Era.”American Philosophical Society 58/9 (1968): 1–58.

Born, Robert. The Sultan’s World: the Ottoman Orient in Renaissance Art. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2015.

Boström, Hans-Olof. “Philipp Hainhofer and Gustavus Adolphus’s Kunstschrank in Uppsala.” In The Origins of Museums, the Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Europe, edited by Oliver Impey and Arthur MacGregor, 90–101. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985.

Burschel, Peter. “A Clock for the Sultan.”The Medieval History Journal 16,2 (2013): 547–563.

Busbecq, Ogier Ghislain. The Turkish Letters of Ogier Ghiselin De Busbecq. Translated by Karl A. Roider. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

Carinthia, Hermann of, Robert of Chester, Johann Albrecht Widmanstetter. Mahometis Abdallae filii theologia dialogo explicatam. Nuremberg, 1543.

Cod. Guelf 206 Blank, (before 1579). Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel.

Diemer, Peter and Dorothea Diemer, eds. Die Münchner Kunstkammer. 3 vols. Munich: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2008.

Distelberger, Rudolf. “The Habsburg Collections in Vienna During the Seventeenth Century.” In The Origins of Museums, the Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Europe, edited by Oliver Impey and Arthur MacGregor, 39–46. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985.

Dünninger, Eberhard, ed. Handbuch der Historischen Buchbestände in Deutschland. Hildesheim: Olms-Weidmann, 1996.

Gadawil al-nisbah al-sittiniyah ’ala al-tamam wal-kamal (Mathematical calculations tables), Anonymous, copying date 1175 H = 1761 CE.

Çağman, Filiz and Zeren Tanındı. The Topkapı Saray Museum: The Albums and Illustrated Manuscripts. Translated by J. M. Rogers. London: Thames and Hudson, 1986.

Faroqhi, Suraiya. Approaching Ottoman History: An Introduction to the Sources. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Fučíková, Eliška. “The Collection of Rudolf II at Prague: Cabinet of Curiosities or Scientific Museum?” In The Origins of Museums, the Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Europe, edited by Oliver Impey and Arthur MacGregor, 63–70. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985.

Göllner, Karl. Turcica: die europäischen Türkendrucke des XVI. Jahrhunderts. 3 vols. Baden-Baden: Koerner GmbH, 1978.

Gundestrup, Bente, ed. Det kongelige danske Kunstkammer 1737 = The Royal Danish Kunstkammer 1737. 3 vols. Copenhagen: Kongelige Danske Kunstkammer, 1991.

Haase, Claus-Peter. “An Ottoman Costume Album in the Library at Wolfenbüttel, Dated Before 1579.” In 9. Mittelerarasi Türk Sanatlan Kongresi/ 9th International Congress of Turkish Art, Bildiriler/ Contributions, vol. 3, 225–234. Ankara: T. C. Kültür Bakanliği, 1995.

Harbeck, Hans. Die Krönungen Maximilians II. zum König von Böhmen, Römischen König und König von Ungarn. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1990.

Inventarium über die Türkische Cammer. Dresden, 1674.

Inventarium über Die Türcken Cammer. Dresden, 1683.

Johnson, Carina L. Cultural Hierarchy in Sixteenth-Century Europe: the Ottomans and Mexicans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Kaufmann, Thomas. Türckenbüchlein: Zur christlichen Wahrnehmung türkischer Religion in Spätmittelalter und Reformation. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008.

Karl, Barbara. Treasury, Kunstkammer, Museum: Objects from the Islamic World in the Museum Collections of Vienna. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2011.

Landtsheer, Jeanine de. “Forgotten letters from Hugo Blotius to Justus Lipsius in Vienna ÖNB, MS. 9490.”Humanistica Lovaniensia 61 (2012): 319–331.

Louthan, Howard. The Quest for Compromise: Peacemakers in counter-reformation Vienna. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Mazal, Otto, ed. Bibliotheca Eugeniana: Die Sammlungen des Prinzen Eugen von Savoyen: Ausstellung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek und der Graphischen Sammlung Albertina. Vienna: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, 1986.

Meyer zur Capellen, Jürg and Serpil Baĝci. “The Age of Magnificence.” In The Sultan’s Portrait: Picturing the House of Osman, edited by Selmin Kangal, 96–102. Istanbul: Isbank, 2000.

Molino, Paola. “Ein Zuhause für die Universalbibliothek: vom ‚Museum generis humani Blotianum‘ zur Gründung der Hofbibliothek in Wien am Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts.”Biblos 58 (2009): 23–39.

Necipoğlu, Gülru. Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power: The Topkapi Palace in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991.

Novigradt die groß Vestung eingenommen: Warhaffte Zeyttung, der abermals in Vngern auß Gottes gnaden, vn[d] Ritterlicher hand erhaltener Victoria, auch was sich bey groß Novigradt, welche den 9. Martij dises 1594. Jars erobert. Nürnberg: Leonhard Heußler, 1594.

Oborni, Térez. “Die Herrschaft Ferdinands I. in Ungarn.” In Kaiser Ferdinand I., Aspekte eines Herrscherlebens, edited by Martina Fuchs and Alfred Kohler, 147–166. Münster: Aschendorff, 2003.

Otho, Liborius. Katalog der Wolfenbütteler Bibliothek. Wolfenbüttel, 1613/14.

Paas, John Roger. The German Political Broadsheet, 1600–1700. Vol. 11. Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz, 2012.

Perjés, Géza, Mário D. Fenyő, and János M. Bak. The Fall of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary: Moháchs 1526 - Buda 1541. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989.

Pfaffenbichler, Matthias. “Orientalische und orientalisierende Waffen.” In Im Lichte des Halbmonds, edited by Claudia Schnitzer and Alfred Auer, 96–100. Dresden: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 1995.

Quiccheberg, Samuel. Der Anfang der Museumslehre in Deutschland: das Traktat „Inscriptiones vel Tituli Theatri Amplissimi“ von Samuel Quiccheberg: lateinisch-deutsch, edited and translated by Harriet Roth. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2000.

Quiccheberg, Samuel. Inscriptiones vel tituli Theatri amplissimi, complectentis rerum universitatis singulas materias et imagines eximias […]. Munich: Adamus Berg, 1565.

Qurʾān - BSB Cod.arab. 1. Sevilla, 1226 CE = 624 H. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek: Hss Cod.arab.1.

Raby, Julian. “Exotica from Islam.” In The Origins of Museums, the Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Europe, edited by Oliver Impey and Arthur MacGregor, 251–258. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985.

Rasmussen, Stig T., ed. Den Arabiske Rejse 1761–1767 – en dansk ekspedition set i videnskabshistorisk perspektiv. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1990.

Registratur der bucher in des Churfursten zu Saxen liberey zur Annaburg 1574 – SLUB Dresden: Bibl.Arch.I.Ba, Vol. 20: der erste Katalog der Bibliothek des Kurfürsten August; Faksimile und Transkription. Dresden: Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, 2010.

Rebhan, Helga. “Die Bibliothek Johann Albrecht Widmanstetters.” In Die Anfänge der Münchener Hofbibliothek unter Albrecht V., edited by Alois Schmid, 112–131. Munich: Wissenschaftliches Symposion, 2009.

Sandbichler, Veronika. Türkische Kostbarkeiten aus dem Kunsthistorischen Museum. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 1997.

Scheicher, Elisabeth. “The Collection of Archduke Ferdinand II at Schloss Ambras: Its Purpose, Composition and Evolution.” In The Origins of Museums, the Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Europe, edited by Oliver Impey and Arthur MacGregor, 29–38. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985.

Scheicher, Elisabeth. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Sammlungen Schloss Ambras, Die Kunstkammer. Innsbruck: Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, 1977.

Scheicher, Elisabeth. “Historiography and Display, the ‘Heldenrüstkammer’ of Archduke Ferdinand II in Schloss Ambras.”Journal of the History of Collections 2 (1990): 69–79.

Schnitzer, Claudia and Alfred Auer, eds. Im Lichte des Halbsmonds: das Abendland und der türkische Orient. Dresden: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 1995.

Schuckelt, Holger. Die Türckische Cammer: Sammlung orientalischer Kunst in der kurfürstlich-sächsischen Rüstkammer Dresden. Dresden: Sandstein, 2010.

Schweigger, Salomon. Ein newe Reiß Beschreibung auß Teutschland nach Constantinopel und Jerusalem. Nuremberg: Lantzenberger, 1608.

Schweigger, Salomon, trans. Alcoranus mahometicus, das ist: Der Türcken Alcoran, Religion und Aberglauben. Auß welchem zuvernemen, wann unnd woher jhr falscher Prophet Machomet seinen ursprung. Nuremberg: Halbmayer and Lochner, 1616.

Seelig, Lorenz. “The Munich Kunstkammer, 1563–1807.” In The Origins of Museums, the Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Europe, edited by Oliver Impey and Arthur MacGregor, 101–119. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985.

Seibold, Gerhard. Hainhofers „Freunde“: das geschäftliche und private Beziehungsnetzwerk eines Augsburger Kunsthändlers und politischen Agenten in der Zeit vom Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts bis zum Ausgang des Dreißigjährigen Krieges im Spiegel seiner Stammbücher. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 2014.

Seipel, Wilfred. Der Kriegszug Kaiser Karls V. gegen Tunis: Kartons und Tapisserien. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 2000.

Seipel, Wilfred, ed. Kaiser Karl V. (1500–1558): Macht und Ohnmacht Europas / Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien. Geneva: Skira, 2000.

Seipel, Wilfred, ed. Kaiser Ferdinand I. 1504–1564. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 2003.

Syndram, Dirk, Martina Minning and Jochen Vötsch, eds. Die kurfürstlich-sächsische Kunstkammer in Dresden (1587, 1619, 1640, 1741). Dresden: Sandstein-Verlag, 2010.

Turnbull, Stephen. The Art of Renaissance Warfare, From the Fall of Constantinople to the Thirty Years War. London: Greenhill Books, 2006.Turnierbuch, Erzherzog Ferdinand II. Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Kunstkammer, 5134.Vienna, Austrian National Library. Codex 3325.Vienna, Austrian National Library. Codex 8615.

Vienna, Austrian National Library. Codex 8626 (after 1590).

Vocelka, Karl. Rudolf II. und seine Zeit. Vienna: Böhlau, 1985.

Vocelka, Karl. Die Politische Propaganda Kaiser Rudolfs II. (1576–1612). Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1981.

Von Eroberung dreyer Vestungn in ober Ungern, der Stadt Watzen, in der Wallachey, der Stadt Claudi und in Dalmatia, der Vestung Casta Nauico sambt der verzeichnus was ordentlich dabey fürgelauffen ist. Prag: Schumann, 1596.

Vos, Lambert de. Das Kostümbuch des Lambert de Vos: vollständige Faksimile-Ausgabe im Originalformat des Codex Ms. or. 9 aus dem Besitz der Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Bremen, edited by Hans-Albrecht Koch, 2 vols. Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, 1991.

Wade, Mara Renée. Triumphus nuptialis danicus: German court culture and Denmark; the “great wedding” of 1634. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1996.

Wappenschmidt, Friederike. “Exotica aus Fernost im Münchner Kunstkammerinventar von 1598.” In Die Münchner Kunstkammer, edited by Peter Diemer and Dorothea Diemer, Vol. 3, 293–310. Munich: Verlag der Bayerischen Akadamie der Wissenschaften, 2008.

Watanabe-O’Kelly, Helen. Court Culture in Dresden: From Renaissance to Baroque. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002.

Weigel, Hans. Habitus praecipuorum populorum, tam virorum quam foeminarum Singulari arte depicti. Trachtenbuch; darin fast allerley und der fürnembsten Nationen, die heutigs tags bekandt sein, Kleidungen beyde wie es bey Manns und Weibspersonen gebreuchlich, mit allem vleiss abgerissen sein, sehr lustig und kurtzweilig zusehen. Nuremberg: Weigel, 1577.

Wieden, Brage bei der. “Was der Herzog erhoffte: die Gründung der Universität Helmstedt.” In Das Athen der Welfen die Reformuniversität Helmstedt 1576–1810, edited by Jens Bruning and Ulrike Gleixner, 38–45. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz in Komm, 2010.

Wilkinson, Robert J. Orientalism, Aramaic and Kabbalah in the Catholic Reformation: the first Printing of the Syriac New Testament. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

Wilson, Bronwen. “Foggie diverse di vestire de’ Turchi: Turkish Costume Illustration and Cultural Translation.”Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 37/1 (2007): 97–139.

Turcica in North and Central European Libraries and Kunstkammers